The right to have a choice. Whichever that choice may be.

The right to not get pregnant, to get pregnant, to end a pregnancy. The right to have control, to have pleasure, to have access to contraception. The right to not be questioned, to not be jeopardized, to not be judged. The right to have a choice. Whichever that choice may be.

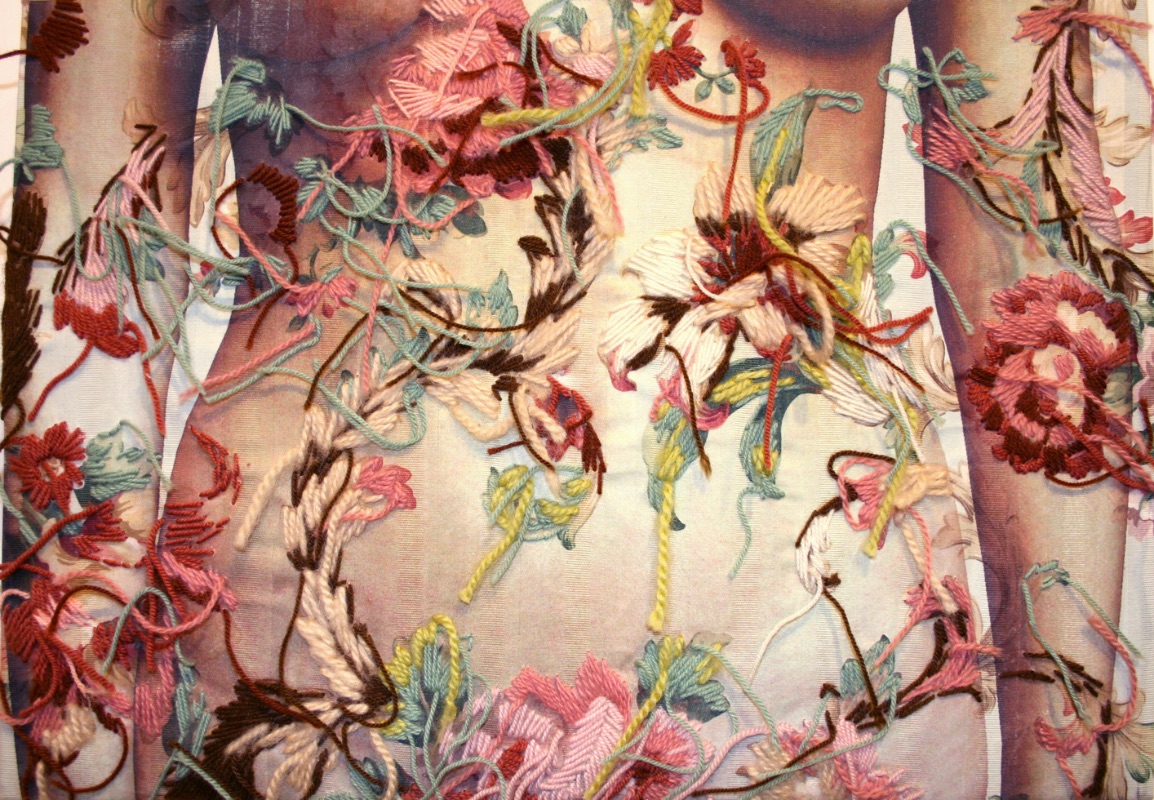

© Photography and embroidery by Teresa Barboza.

© Photography and embroidery by Teresa Barboza.

“Woman? Very simple, say those who like simple answers: She is a womb, an ovary; she is a female: this word is enough to define her.” The words are by Simone de Beauvoir and it’s with them that one of the most influential feminist authors and thinkers of her time (and our time alike) begins the powerful ‘The Second Sex’, published in 1949. More than seventy year have gone by. Today, and unlike what happened in 1949, women can have a credit card under their names, study at universities like Yale, Harvard and Princeton, talk openly about sex, have access to the pill and, in many cases, obtain a legal abortion.

More than seventy year have gone by. Today, as women, we have more freedoms, more rights, more options. We can buy our own contraceptive methods with our own credit cards. We can go to college, take a year off, have a career. We can have an opinion. We can have more than one opinion. We can speak up. We can go out on the street, we can protest, we can demand. We can be independent, but we can also choose not to be. We can be single, but we can also choose to be committed. With one person, two people, three people. With whoever we want. We can live alone, but we can also choose to share our space. We can get married, but we can also say no to matrimony. We can discuss our sexuality, our pleasures, our desires. We can get pregnant and be mothers. We can choose to not get pregnant and still be mothers. We can choose to not get pregnant and be as happy, or even more happy. We can put an end to a pregnancy without putting an end to life. We can be unsure of what we want and still be able to preserve our fertility.

Written this way, it seems like we can have it all – and we can, we really can. We have freedoms, we have rights, we have options. But if we have the freedoms, the rights and the options, why is there a little voice behind our ears that keeps on repeating that same Simone de Beauvoir sentence: “Woman? Very simple, say those who like simple answers: She is a womb, an ovary; she is a female: this word is enough to define her.” If we have the freedoms, the rights and the options, why does society still try to determine what we should or shouldn’t do with our bodies? What we should or shouldn’t want for our bodies?

"In the eyes of society, there’s no right answer when it comes to having kids."

“In the last few years, we’ve made massive strides towards acceptance and inclusion: from legalizing gay marriage to speaking up about misogyny and racism. But there are still some lives you can lead in 2016 that will bring judgment and condescension to your door as if it were still the 1950s - one of those is being a woman without kids and an even bigger one is being a woman who doesn’t want kids. There are a lot of women affected by society’s crappy judgment in this regard: those who haven’t had kids yet, those who want them and haven’t been able to have them, and those who never want them ever - like me. I probably get the easiest ride, as someone who’s never wanted kids and consequently had her tubes tied at the age of 30, leaving the tags on my unused womb.” Titled ‘Why Is Society Still So Afraid Of Women Who Don’t Want Children?’, this opinion piece by journalist Holly Brockwell for Grazia is one of the many testimonies of its kind – meaning, about the way that women who don’t want to follow the path of maternity are still seen by society.

“I’ve been belittled, insulted and threatened over my choice, in part because I spoke up about it publicly. But the attitudes that cause strangers to send me Facebook messages saying I’m a slut because I want to have sex with my partner without worrying about unwanted children, are the same ones driving people to make intrusive and wounding remarks to women who would love to be mothers, but haven’t got there yet. In the eyes of society, there’s no right answer when it comes to having kids. You’re not allowed to have none (selfish), you can’t have only one (cruel) and you certainly shouldn’t have ‘too many’, especially if you’ve ever used this country’s benefits system that you’re entitled to, to help cope in the early years of parenthood. We seem to be in an enormous hurry to make everyone get pregnant, anyone considered to be dawdling or delaying can expect probing comments and looks of faux-sympathy from every damn person they encounter, from relatives to randoms.”

Even though maternity is profoundly rooted in our society, it’s quite problematic that something so personal is seen as an expectation rather than a choice that each and every woman should be able to make on her own terms. Even though maternity is profoundly rooted in our society, it’s quite problematic that we still question the decision of a woman who chooses not to have children – be it for financial reasons, emotional reasons, environmental reasons (yes, you can choose to not have kids in order to save the planet) or for the simple reason that, for no reason in particular, she doesn’t want to have children. Even though maternity is profoundly rooted in our society, it’s quite problematic that we still look at women who don’t want to get pregnant as broken women. As abnormal and immoral women. As women who will never be completely happy of completely fulfilled. As women who don’t like children. As women that don’t know what they want, as women who are too young to know what they want. As women who will regret it one day – and when they do it will be too late.

"Apparently, a woman who doesn’t want kids is a shocking thing, even in 2019."

“I also didn’t have a clue that being vocal and confident about this decision would elicit the critical feedback it has over the years. People I knew and people I didn’t know told me that I’d change my tune as I got older. No one trusts women (let alone 18-year-old women) to know their own bodies and minds. And though I understood that some people who make this decision evolve their stance over time — or find a partner who cares more deeply about having children than they do about not having them — something told me I wasn’t going to.” The words were written by journalist and author Erica Cerulo in the piece ‘I’m Never Having Children—Why Does That Make You So Upset?’, published in Refinery29 on October of 2019.

“Apparently, a woman who doesn’t want kids is a shocking thing, even in 2019. (...) Though I feel as strongly at 36 as I did at half that age, I’ve had to validate my stance through the years. I’ve had hard talks with family members who’ve said, 'But you’d be such a good mom.' To which I respond: 'I’m a firm believer that you shouldn’t do something just because you’re good at it.' (After all, I could be a really great tightrope walker too, but we’ll never find out.) I’ve corrected relatives who’ve said, 'Just wait ‘til you have your own!' while chasing a toddler around a living room. I’ve braced for monologues about how being a parent has been the most meaningful experience in one’s life — as if that insight might trump me following my gut. On a business trip, I’ve put a co-worker in his place after he chuckled and said, 'We’ll see,' when hearing my intentions. I’ve had awkward exchanges with a hair stylist, who asked soon after I got married when I was going to start trying for a baby, and I’ve had ridiculous interactions with practical strangers who felt infuriatingly comfortable sharing their opinions on what I do with my body. Just the other week, a man I’d known for five minutes asked if I saw that study that reported women who don’t have kids are judged more harshly. Weirdly, I didn’t request he send it to me.”

She continues: “I want to feel supported in my decision and to support everyone else in theirs. Because ultimately this is about choice, right? The people who matter most to me (my parents very much included) get that by now. But I want the Gloria Steinem quote 'Not everybody with a womb has to have a child, like not everybody with vocal cords has to be an opera singer' to feel like a big, ol’ duh to everybody. I want to be a parenthood ally and to understand pregnancy and birth better, because doing so is essential to advancing women on the whole. I want to be able to have informed, supportive conversations with friends about IVF. I want to make the workplace better for parents, and every last one of us whose personal life calls for flexibility and compassion within our professional life. But I also want to go home to a quiet apartment and to never, ever feel guilty, insecure, or judged for doing so.”

"Legal abortion means that the law recognizes a woman as a person. It says that she belongs to herself."

“Woman? Very simple, say those who like simple answers: She is a womb, an ovary; she is a female: this word is enough to define her.” More than seventy year have gone by. As The Atlantic wrote earlier this year, “from China’s ‘leftover women’ [a term used by the government to describe women that are more than 27 years old and unmarried] to Israel’s ‘baby machines’ [an expression used by filmmaker Shosh Shlam to describe the role of orthodox women], society still dictates female lives” – and, by doing so, what a woman can or not do with her own body. In 2019, the New Yorker published an in-depth investigation about IVF laws in Poland, where single women and gay couples are denied the treatment. “Seen through a feminist, progressive lens, assisted reproductive technologies have emancipatory potential; they have the power to expand the definition of family, creating new familial configurations and notions of relatedness. Poland’s IVF law, by contrast, suggests what can happen when such technologies take root in a society that’s determined to remain traditional. Single motherhood is neither new nor radical; women have always raised children on their own, for any number of reasons (death, abandonment, divorce). The law, in attempting to preserve a narrow notion of what a family should be, has had the perverse effect of severing the mother-child bond. A government that confiscates a mother’s embryos so that it can encourage only the 'right' kinds of families creates its own kind of brave new world”, wrote Anna Louie Sussman. In that same year, the United States were taking a huge step back in regards of women’s sexual and reproductive rights. The state of Alabama passed a near-total ban on abortion (the only exception being when the woman’s healt is at serious risk), the most restrictive law in the United States; in Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi and Ohio passed so-called “heartbeat bills”, which ban abortion once a fetal heartbeat can be detected, closing the window to six weeks, when most women still don’t know they are pregnant. The goal? Overturn Roe v. Wade.

“Legal abortion means that the law recognizes a woman as a person. It says that she belongs to herself”, wrote poet and essayist Katha Pollitt in The New Yorker. “So, if women who have never had an abortion, and don’t expect to, think that the new restrictions and bans won’t affect them, they are wrong. (...) Without legal, accessible abortion, the assumptions that have shaped all women’s lives in the past few decades—including that they, not a torn condom or a missed pill or a rapist, will decide what happens to their bodies and their futures—will change. Women and their daughters will have a harder time, and there will be plenty of people who will say that they were foolish to think that it could be otherwise.” And as Emma Sarran Webster wrote in a Teen Vogue piece, “as people across the United States fight to maintain the right to legal birth control and abortions, many women are already suffering the loss of reproductive autonomy within their intimate relationships as victims of reproductive coercion” – a “type of abuse that involves an abuser exerting power and control over a victim’s health and reproductive decisions” that can go from hiding, destroying of withholding contraception; poking holes in a condom or taking it, without consent, during sexual intercourse; or physically removing contraceptives such as the IUD or the vaginal ring. As Emma puts it, “while it’s not a particularly mainstream term at this point, it’s actually quite common — particularly among young women. A study conducted by researchers at University of Pittsburgh and Michigan State University (MSU) and published this year in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology,found that nearly one in eight sexually active females between the ages of 14 and 19 had experienced reproductive coercion in the last three months alone. A 2011 survey of more than 3,000 people conducted by The National Domestic Violence Hotline found that 25% of participants had experienced this type of abuse in some form”.

We have freedoms, we have rights, we have options. And it’s precisely because we have those freedoms, those rights and those options that, in 2020, the discussion should be as simples as this: my body, my choice. But while we're not there yet, we'll keep on saying it, for as long as we need to: my body, my choice.

This article was originally published in Vogue Portugal's Freedom on Hold issue, from April 2020. Para ler este artigo em português, veja a edição Freedom on Hold, de abril de 2020, da Vogue Portugal.

Most popular

.jpg)

.png)

Relacionados

.jpg)

Sapatos de noiva confortáveis e elegantes: eis os modelos a ter em conta nesta primavera/verão

24 Apr 2025