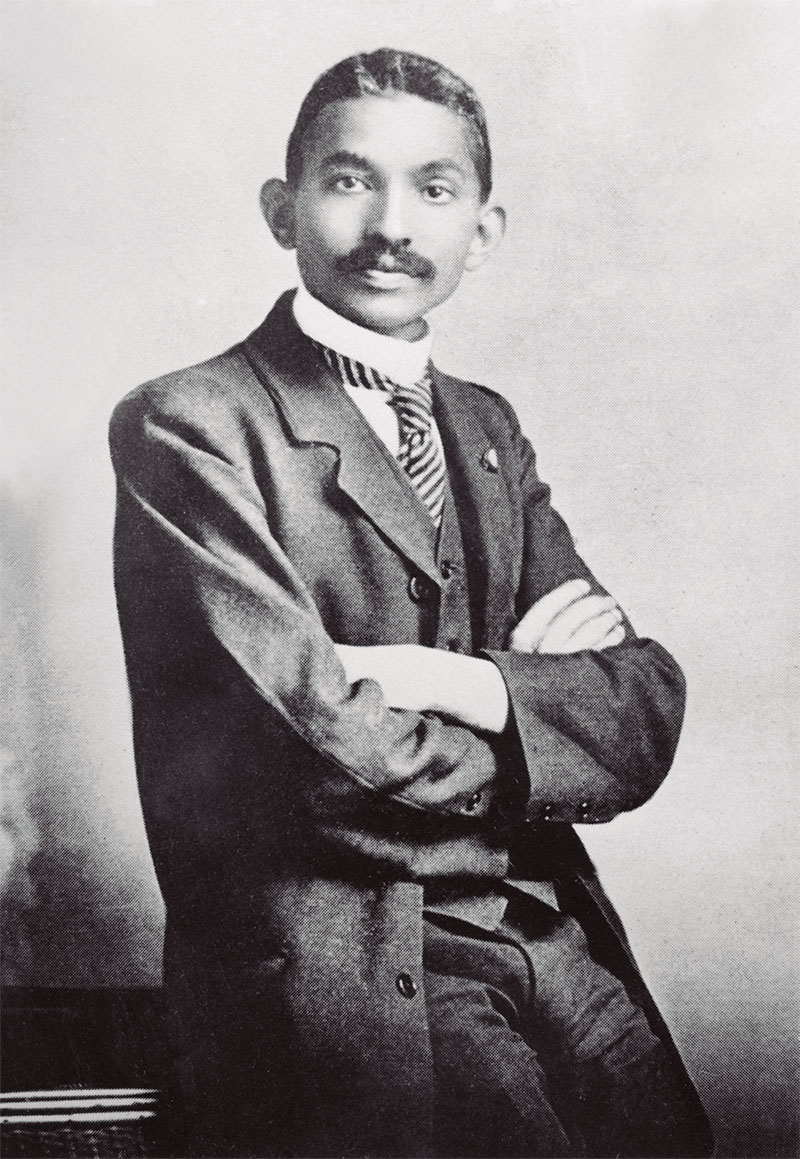

From the image of a gentleman to the humblest of men, Mahatma Gandhi kept a symbolic and profound relationship with clothes throughout all his life.

From the image of a gentleman to the humblest of men, Mahatma Gandhi kept a symbolic and profound relationship with clothes throughout all his life. Bandana Tewari traces the details of this fascinating story and the lessons the Fashion world may learn with the man that was one of the greatest political and spiritual leaders of the 20th century.

Gandhi and fashion? It sounds incongruous and absurd. But fact is better than fiction, and in this case, there is a lesson to be learned about the socio-political significance of our clothes, or what we can simply discuss within the realm of fashion - sartorial integrity.

Today I would like to overlay this route of opulent silks with a humble cotton thread, called Khadi. For Mahatma Gandhi, Khadi— the hand-spun, handmade cotton, common to India, Pakistan and Bangladesh was a metaphor for mindful consumption. Gandhi started out as an Indian lawyer journalist-activist, who became a politician and leader of the nationalist movement that gained freedom from British colonization. In India, he is called The Father of the Nation. There was a time when Winston Churchill, called him the ‘Half-naked Fakir'—a fakir, the poorest of the poor, clad in a frugal piece of cloth-called the loin-cloth, a piece of hand-spun fabric that he wrapped around his waist. And nothing else.

So why Gandhi and fashion? What did he have to do with the world of fashion and luxury? Gandhi’s relationship with clothes was deeply profound and symbolic. In my research, I found a fascinating essay by Professor Peter Gonsalves from Rome University titled: 'Half Naked Fakir'-The Story of Gandhi's Personal Search for Sartorial Integrity.

‘Search for Sartorial Integrity’ is not what the fashion industry, as we know it today, really focuses on, I argued. But Professor Gonsalves explains, sartorial integrity is the deep exploration of truth through clothes. He explains that in Gandhi’s quest for truth and authenticity in his social, economic, political and ideological thoughts and actions, his clothes played a powerful role, that till date holds up a mirror to the realities of our luxury world and the challenges of consumerism.

London Chapter

The clothing journey began in India. From a very young age Gandhi was quite the dandy imitating the English codes of dressing in order to be perceived as respectable in his attire mimicking the fineries of an English gentleman. His clothing also demonstrated his family’s social, political and financial stature. Then Gandhi left for London to study law. He was acutely shy and fearful of being ridiculed because of his clothes. When he reached Southampton he was teased about his flannels. He was a strict vegetarian which caused great deal of embarrassment to his friends. To compensate for this social disadvantage, he went all out to be the perfect English gentleman. He took lessons in elocution, dancing and playing the violin. When Gandhi returned to India his elder brother, spent a lot of money to create an English atmosphere in the home and Gandhi is said to have "put the finishing touch" by introducing oatmeal porridge and cocoa to his Indian breakfast! The notion of Indian-ness or Indian identity hadn’t stirred yet as Gandhi believed by conforming to prevailing western fashions he was likely to be socially acceptable.

South Africa Chapter

Feeling suitably gentrified and confident in his new polished style he moved to South Africa to practice law. In South Africa he was in for rude shock. There were two types of Indians in South Africa—gentrified ones like him, educated and affluent; and the poor Indian laborers, slaves in a bigoted country. Not only were Indians in European clothes a strange sight, Gandhi learnt that Indians in ‘decent’ Indian attire were also unacceptable. When one day Gandhi was thrown out of the train, he realized neither his first-class ticket nor his European attire could convince the white policeman that he was “decent” enough to travel at will. But even at this point in his life, Gandhi couldn’t understand why the white South Africans and the government could not make a distinction between well-dressed, well-educated Indians and Indians who were poorly dressed and worked as menial laborers. Then one day he ran into an Indian laborer - Balasundaram, who was beaten black and blue, with his teeth missing, holding a bleeding head. This left an indelible mark on his conscience. He was suddenly struck by the shallowness of his life based on prestige and appearances. This was a turning point in Gandhi’s life.

During the course of his 20 odd years in South Africa, Gandhi began his quest for truth and authenticity of being. He studied the plight of the poor laborers, and galvanized the Indians (both rich and poor) to stand up against a bigoted government. He worked as a nurse during the Boer War in South Africa to understand human suffering. He experimented with community living- in farms, simplifying his life and focussing on selfless service and self-empowerment—which later became the benchmark of SWADESHI— a movement of self-reliance that played a pivotal role in India’s freedom struggle.

It was during this time of self-purification that he decided as an extension of his beliefs, it was only appropriate for him to choose a sober costume that would symbolize his life-changing commitments. He called it the 'mourning robe'— white kurta (tunic) and dhoti (the white sarong). His change of dress became a symbol of SATYAGRAHA- or ‘truth force’ that identified itself with those who were the invisible, the poor in our societies who suffer silently.

India Chapter

On his arrival in India, He travelled the length and breadth of the country to understand the woes of the common man. He saw that under British colonization the country had been depleted of its resources and its spirit. One of the biggest movements directly related to clothes was The Khadi Movement.

Historically, the Indian local economy was all about traditionally made textiles. Each village had its spinners, dyers, and weavers who were the heart of the village economy. During colonization, the British colonizers would buy cotton at cheap price from India, export them to Britain where cotton was woven into clothes. These clothes (today’s fast fashion?) were then sent back to India and sold at a hefty price to the Indians, only to profit the colonizers. . When India was flooded with machine-made, inexpensive, mass-produced textiles from Lancashire, the flourishing local textile industry was rapidly put out of business; and the true strength of India- the village economy- devolved from wealth to penury.

This oppression motivated Gandhi to start a nation-wide campaign called The Khadi Movement to restore the livelihoods of millions. He asked an entire nation- India- to discard and burn the factory-made clothes as an act of civil disobedience without violence. He asked every person to spin their own yarn and weave their own cloth. The nation responded. Thousands of villages across India started weaving their own cloth as a sign of protest! This made the mills in the UK come to a grinding halt. This was the nation’s call for dignity of labour through Swadeshi or self-reliance. The spinning wheel or the Charka became the symbol of economic freedom and political independence.

But Gandhi, who was still fully clothed at this stage of his life, felt he had no moral right to ask the poorest of the poor— ones who couldn’t afford to burn mill-made clothes because they had none— participate in the freedom struggle for independent India. And as an act of extreme humility and solidarity with the poor, he discarded all his clothes except for the lion-cloth, a humble piece of handmade fabric called khadi. Professor Gonsalves calls this an act of making one’s personal morality transparent to the whole world, even through one's dress. So when Winston Churchill called Gandhi ‘ a fakir’ the poorest of the poor, Gandhi took that as a compliment. What he wore became a symbol, the moral compass of his beliefs and his commitment to the poorest of the poor.

This transformed Gandhi from an English dandy to India's Mahatma. ‘Maha’ means ‘great’ and ‘Atma’ means soul—a great soul. This is a remarkable story without parallel in the political history of the world. To Gandhi, Clothing was an essential part of his inner quest for truth. In his process of robing and disrobing, he developed principles and practices which we will examine now to see how it applies to the fashion and luxury businesses of today. Gandhi was convinced that social inequalities could only be won by the power of SATYA-truth and AHIMSA- non-violence and SWADESHI- self-reliance. These may sound like idealistic beliefs but he turned them into mass socio-political movements, where an entire nation participated to fight for freedom by means of non-violent protest and civil disobedience.

So what can the luxury industry learn from Gandhi’s SWADESHI or self-reliance movement? In the luxury business, we put Made by Hand, Hand-made, Craft-centric design on top of the pyramid of creativity. But the ‘cult’ of handmade, especially in Asia, brings village economies centre stage – as most south Asian countries are rural, agrarian and artisanal. Swadeshi or self-reliance became the Gandhian way of ensuring that these artisanal villages continued to create and thrive withintheir own village eco-system. This was the strength of grass-root economies built from ground -up, that Gandhi believed in, which made nations rich and resilient because he believed in the village ‘units’ that made the whole.

Countries like India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Cambodja, Vietnam, Indonesia all part of the famous Silk Route have been at the epicenter of local crafts and continue to be so. But most of these countries are also becoming victims of a centralized and industrialized economic system, that is replacing handmade for machine-made; and indigenous skills replaced to benefit assembly line fast fashion.

For Gandhi, Swadeshi was a program for long-term survival. He envisioned a decentralized, home-grown, hand-crafted mode of production. In his words, "Not mass production, but production by the masses."Where each village would thrive in their own eco-system of skills, services, production and distribution. He believed that each village should be a microcosm of its nation. Gandhi wanted to give them the status of "village republics".

Today, in India alone, approximately 11 million people (7 million weavers) in Indian villages are creating with their hands- as weavers or handicraft-artisans every day. If we don’t empower the artisanal villages of the world, then we will see the last of the craftsmen in their own habitat, the migration of new generations to already over-populated urban areas, and an erosion of indigenous skills. Gandhi believed in the idea of SARVODAYA- welfare for all. But this cannot happen if we look at each other's countries as just sources for raw materials, sources for cheap labour, sources for extraordinary made-by-hand textiles, embroideries and embellishments for which they get little credit. We need to give dignity of labour to the craftspeople of the world. We need to bring humanity to what can be a beautiful, fulfilling communion between creator, producer and user. That would be a Gandhian approach to the luxury business.

The fundamental guiding principle that was the foundation of Gandhian philosophy was AHIMSA OR NON-VIOLENCE. Ahimsa refers to non-injury in thoughts, words and deed. He said: “Non-violence is not a garment to be put on and off at will, its seat is in the heart and it must be inseparable part of our very being”. Our business is the second largest pollutant after oil and gas and its imperative that we weave the thread of Ahimsa into the tapestry of fashion. Ahimsa goes to the heart of our dialogue on sustainability and the ethics of fashion production. It holds up a mirror to our technological progress and industrialization. On a fundamental level it asks us if our systems and patterns of consumption are non-violent. Will it continue to be linear systems, of ‘fast’ unscrupulous production, consumption and disposal, creating extraordinary waste and damage to our environment? Or are we creating circular systems where the end of one life-cycle of a product becomes the starting point for another life-cycle?

Gandhi believed in the idea of APARIGRAHA- one of the 11 vows that he took. It means we are mere “trustees” or custodians and not owners of our environment and we owe to ourselves to pass on the environment to the next generation in a good condition. Gandhi’s principles drew considerable attention and followers, in corporate governance, present day capitalism, and particularly in the Green Movement- The deep ecology of Arne Naess, peace research of Johan Galtung and economics of E. F. Schumacher are argued to have been deeply influenced by Gandhi. Now, Ahimsa should be at the heart of a conscious luxury world.

Gandhi was an activist who believed in social change. Today we need a world of Activist Designers who are committed, ideologically, to be a ‘slow thinkers’ and ‘slow creators’. Ahimsa is at the heart of the Slow Fashion Movement—a movement that focuses on quality not “time”. It is not about the speed of making and consuming things; it is Mindful Luxury characterized by long life, authenticity, environmentally-friendly designs created with great sensibility to local crafts and cultures. Gandhi’s quest for authenticity was paramount in his journey of self-discovery. He believed that authenticity was at the heart of truthfulness. Mindful luxury is a farce if it doesn’t provide an authentic experience. If the process is less important than the end-product then we will continue to be fooled by the destructive, resource depleting systems of newness, novelty and the revolving images of ‘disposable fashion’.

Gandhi was called the ‘conscience of humanity” and today connecting to Gandhian philosophy is critical to ensuring we uphold ourselves to a moral responsibility toadopt sustainable and kinder practices. These concepts are by no means alien, but they need to be repackaged and refreshed every so often to stay relevant.

Today, every year 150 billion garments are produced annually, that’s enough to provide each one of you and me, and the entire planet, 20 new garments a year! This should be a reminder to each of us, what Gandhi said three-quarters of a century ago: “The world has enough for everyone’s needs, but not everyone’s greed”.

Translated from Vogue Portugal's Hope issue, out September 2020. All credits in the original articles.Texto em português na edição em print.

Most popular

.jpg)

.png)

Relacionados

.jpg)

Sapatos de noiva confortáveis e elegantes: eis os modelos a ter em conta nesta primavera/verão

24 Apr 2025