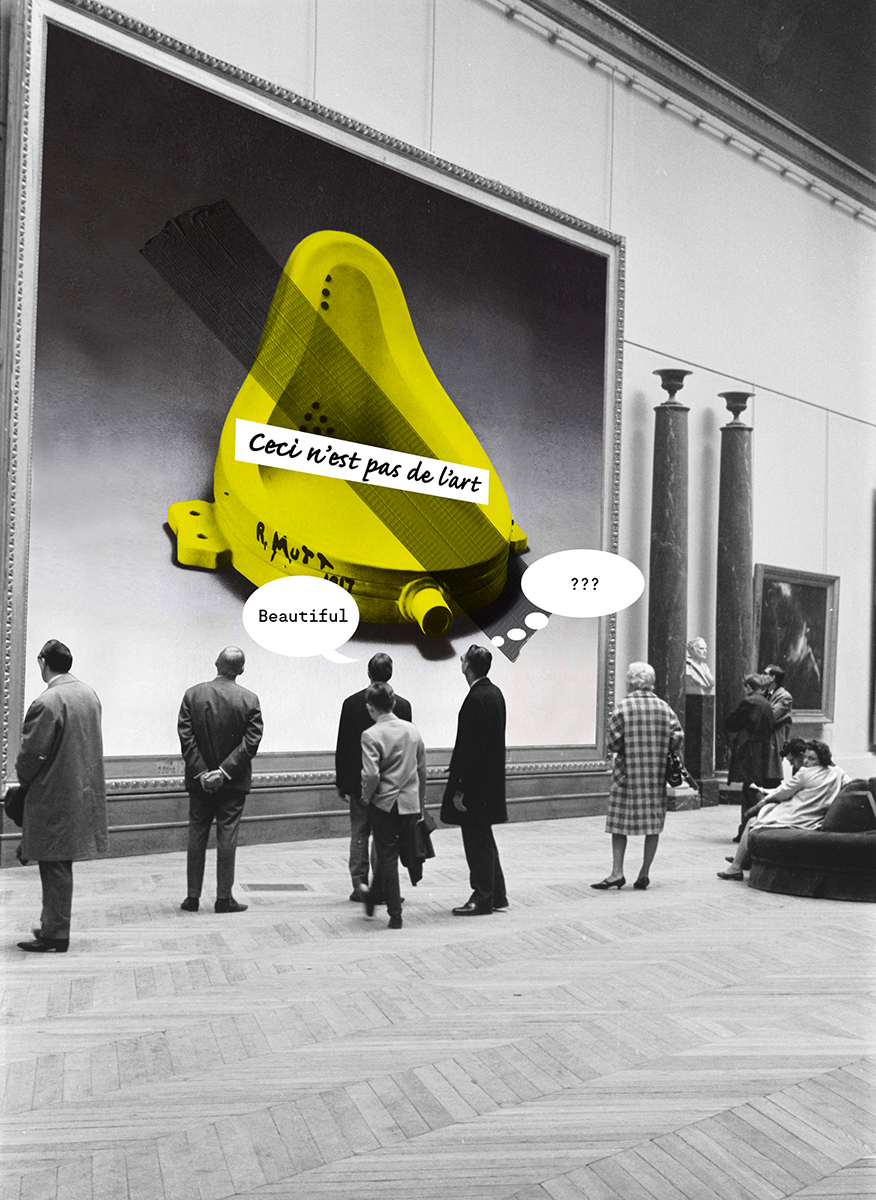

Once upon a time, a urinal became an artistic masterpiece. All of a sudden, it went from being an ordinary piece of bathroom crockery to “the” Fountain. And that changed everything because someone did what no one had ever done before, and even had the audacity to call it art – and art belongs to those who make it.

Once upon a time, a urinal became an artistic masterpiece. All of a sudden, it went from being an ordinary piece of bathroom crockery to “the” Fountain. And that changed everything because someone did what no one had ever done before, and even had the audacity to call it art – and art belongs to those who make it.

Anyone can be an artist. This affirmation, eventually disconcerting, will be corroborated throughout this paragraph. Anyone who had thought about laying a urinal horizontally, for example, calling that object Fountain, and sending the peculiar installation to an exhibition, disdaining any pretentious art critics on sight – anyone who had thought of that would automatically become an artist and anybody could have done it. Anyone can be an artist. Anyone who would have taped a banana to the wall and said “dearly beloved, here it is: I’ve made art” could be an artist. If Andy Warhol made an art piece replicating a Coca-Cola ad, then any individual with a printer can be an artist. There are people making thousands, millions even, auctioning pieces which scream “fool” – Blue Fool (1990), Christopher Wool – to those who watch them. If the secret to making art is to insult those who contemplate it, look no further: I’m a potential genius. Except I’m not a genius, in fact, because I’ve never thought of any of this in time. When I found those ideas, every time I reached them, someone has had them before already. But it could have been me.

Art and Technique

“What? This is art?! If these people are artists, then I’m an artist too.” Those who have never, even if just introspectively, had this sort of outburst may throw the first stone. After all, what makes certain objects artworks? Where does the artistic character lie? It’s not always easy to determine what resides on this side of the spectrum, the one of common human existence, and what is on the other side, into the realm of artistic creation. Let us look at some examples that, for their own peculiarity, demonstrate the blurriness of that line that should clearly distinguish one field from the other. A few years back, at the Sala Murat gallery, in Bari, South of Italy, a cleaning lady threw in the garbage some newspaper sheets and pieces of cardboard that were laying around on the floor. It turns out that those pieces of garbage only looked like garbage: in fact, they were part of an installation by a collective of artists called Mediating Landscape. The poor lady had no idea. It’s ok, insurance covered the damages. Years before, in 2001, at the Eyestorm Gallery in London, yet another cleaning team fulfilled their duty and cleaned away ashes – that were spread all around – of an installation by Damien Hirst which consisted, basically, in empty beer bottles and overflowing ashtrays. Another paper bag and cardboard piece by Gustav Metzger, part of an exhibition at the Tate Gallery, was mistaken by trash and thrown out. As we can see, the line that separates art from non-art is not at all clear. At least, not for the common citizen. How many pieces, interventions, installations might end up being confused with mundane waste if there is no plaque on the side indicating what they’re actually all about? Why is it that if a 5-year-old child tapes a banana to the wall that’s more than enough reason for a reprimand (and some cleaning work), but if Maurizio Cattelan does it, he gets 120 thousand dollars for it? Market questions aside, which work in art as they do in any other sector who might awake attention and interest amongst wealthy people – we should never underestimate the need for the satisfaction of wimps as a motor for the oscillations in any given market. Let’s focus solely on what brings us here, art, that is. If we were to be etymologically accurate, we’d risk underestimating a very big chunk of how much has been created and produced, at an artistic level, since the end of the XIX century. The thing is that the etymological origin of the word art resides in the expression ars, which can be translated to skill, in the sense of dexterity by technique (from the Greek teknè, which can mean both technique and art).

Throughout time, a since a very while back, art affirmed itself in the center of society whether reflecting them or conferring them cultural identity. From culture to culture, it always had a touchpoint with the virtuoso, the mix of talent and mastery of technique. Artworks have obeyed throughout history to the canons of their time and place, though never forsaking the aforementioned definition. The skill, the technique, the dexterity, all those were fundamental components that allowed for the different art expressions that comply with schools and currents thriving in the ways to execute a piece of art. Until, after many centuries of schools and canons, from the development of techniques to represent reality, Modern Art emerged. And it is precisely at this point that the ordinary citizen begins to get confused when, for example, they work in a cleaning team and need to decipher which urinals to Clorox and which not to, which ashtrays to empty and which ones to leave untouched. Not all Modern Art, by deduction, dilutes the frontier that objectively situates an artistic object on one side and a product of daily life on the other. But there is, within that umbrella designation which we know as Modern Art, some movements and currents that tend to make life more difficult for those used to seeing art solely as works of the caliber and detail of Vermeer portraits or Rembrandt compositions. Then, movements and currents like these come along, that allege that art is not merely a showcase of competencies, but also is (or at least most importantly) an expression of feeling. Some go even further, adopting a nearly nihilistic stand when it comes to artistic creation, freeing it from all pretensions – the name Dada perfectly illustrates the goal they proposed themselves to fulfill: it’s meaningless, it has only an illogical expression -, created literary and visual art objects stripped from any meaning or intention. And it’s within that meaningless mix, cooked under the mentorship of Tristan Tzara at the Cabaret Voltaire, in Zurich, that Marcel Duchamp emerged, that same guy that constructed an art piece, when, in 1917, he placed the urinal on the floor and called it Fountain. Art was changing; to create meant much more than just to replicate techniques and copy stencils; to think and to express oneself would take on a role as important, or even more so, than skill, than the domain of technique.

Colombo’s eggs

When, in October 2018, the Sotheby’s auction slammed the hammer and proclaimed “sold!”, the framed painting started to slip through the interior slit of the frame, which contained a paper shredder. Right there, in front of the widely opened eyes of everyone present, the Banksy painting, a replica of the 2002 graffiti Girl With Balloon, was completely destroyed the second it had been bought for 1,4 million dollars (1,15 million euros, according to today’s exchange rate). The debate, as expected, was set on fire: was the destruction of the artwork an integral part of the art piece itself? Was the act of destroying the piece the very own signature of the artist? Had it all been an immense waste of time and an even worse waste of money? After all, making a replica and destroying it doesn’t really require the touch of a virtuoso. Opinions were divided, but the image of the painting self-destructing stuck to our memory. That other piece by Maurizio Cattelan, sold at the Art Basel in Miami, ended up being way cheaper than Banksy’s self-destructing painting. Even so, Comedian, a minimalistic installation that consisted of a scotch-taped banana on a wall, was acquired, as previously mentioned, for 120 thousand dollars, something like 99 thousand euros. Again: it was a banana scotch-tapped to a wall. Examples like these are recurrent in recent history after Modern Art changed the world and didn’t leave another alternative for Contemporary Art except to follow the path past generations trailed before – what other barriers were there to knock down, after Duchamp had sent Fountain, signed “R. Mutt 1917”, to the opening exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists at the Grand Central Palace in New York? But the debate, legitimate and reasonable when we’re faced with a banana taped to the wall that cost nearly 100 thousand euros – which would probably allow for the purchase of around 100 thousand kilos of bananas at any supermarket at market price; or, from another perspective, Cattleman’s piece was sold at 700 thousand euros the kilo -, goes on: why do these pieces, things that, apparently, anyone could be able to do, are considered artworks? The story that follows is apocryphal, but it deserves that we replicate it due to the message it conveys. After having established the marine route to North America, Colombo participated in a feast with the Spanish aristocrats. At a given point, one of the participants would have insinuated that what he, Colombo, had accomplished was not that big of a deal, since any other person in his shoes would have done the same, it all had been a matter of opportunity: the sailor was the right man at the right time. Colombo, calm and collected as possible under the circumstances, didn’t bother to respond. He simply asked for an egg. When it was brought to him, he addressed those sitting at his table: “Gentlemen, I challenge you to place this egg straight on the table”. They all tried, no one managed to do it. Taking the egg again, Colombo slightly tapped the bottom part of the egg, flattening the shell and thus being able to place the egg straight, after which he would have said: “now that you’ve seen how it’s done, anyone can do it” – which is pretty much the same as saying “now that I got it, it looks easy right, you morons?” It’s not certain that all those involved understood the analogy at the time.

What is the point?

The point is to provoke, it’s about the challenge. These pieces are art, not because of their brilliance or aesthetic, but because of the question they raise, that shakes our preconceived knowledge: can this be art? And if by questioning us, bothering us, by being insolent with our sensibility, with our intelligence and perception, by challenging what we think we know and all our rank of prejudice about what constitutes art or not, that the gesture, the thought and, finally, the creator’s object become legitimate: yes, well, of course, it’s art! In the end, all this is a sort of Colombo’s egg. Any one of us could have confronted the world and all its establishments, but it was them and not others that placed urinals on the floor and tapped bananas to the walls – while we were left arguing, obeying to the conventional order of things, with our rachitic, small-minded creativity: “How in the world could this be art? That is no artwork, don’t mess with me. I could do that”.

Translated from the original article of Vogue Portugal's Creativity issue, published in March 2021.

Most popular

.png)

.png)

Relacionados

.jpg)

Como escolher joias para iluminar o rosto? A regra de “ouro” e 5 dicas para brilhar

16 Apr 2025