Talking about art, fashion and the art that is fashion is also talking about - and talking to - Andrew Bolton, the man behind some of the biggest art exhibitions dedicated to fashion. We don't want to spoil anything, but that's exactly what we did.

Talking about art, fashion and the art that is fashion is also talking about - and talking to - Andrew Bolton, the man behind some of the biggest art exhibitions dedicated to fashion. We don't want to spoil anything, but that's exactly what we did.

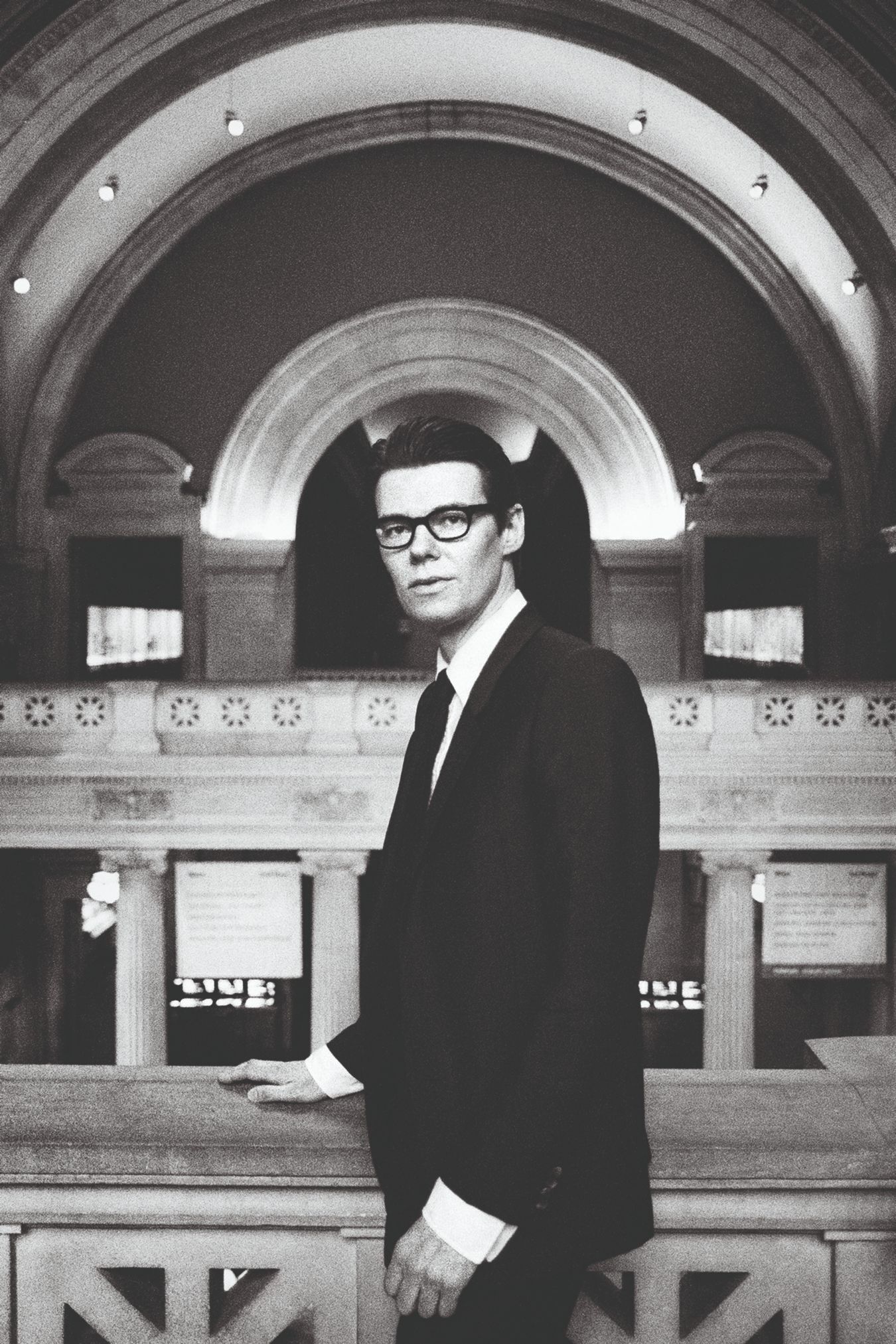

Andrew Bolton © Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Pari Dukovic/Trunk Archive

Andrew Bolton © Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Pari Dukovic/Trunk Archive

There is a moment in The First Monday in May – the 2016 documentary by Andrew Rossi that takes the spectator in a backstage tour of the Met Gala, or as André Leon Talley defines it, the annual event that is the Super Bowl of the fashion industry – where Anna Wintour declares that “it’s rare to find someone so creative that they change the way you look at art”. That someone, as you may have already guessed it, is Andrew Bolton.

The clock strikes 11 am in New Work (4 pm in Lisbon, in a sunny Friday afternoon) when the curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute answers a phone call from the other side of the Atlantic. After I confess to him that it would be very hard to imagine an issue dedicated to Art without the visionary that gave us, in little more than a handful of years, “AngloMania” (2006), “Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty” (2011), “China: Through the Looking Glass” (2015), “Rei Kawakubo/Comme des Garçon: Art of the In-Between” (2017) and “Camp: Notes on Fashion” (2019), the charming voice that speaks from the West end of the line says “we are very excited”. From the long list of questions, and because time is anything but that, comes the first and most obvious: why fashion? “I think it was probably the style magazines that were emerging in the 80s. Magazines like The Face, i-D and Blitz”, says Bolton, the Englishman in New York that grew up in Lancashire, United Kingdom. “The 80s in England were a rich time for fashion, particularly street style and subcultural style. It was a really exciting time to be in England in the 80s because of the impact of subculture in fashion. It really was the subcultural styles in England that caught my interest in fashion initially.”

What happened next is very well documented in that enormous museum called the Internet – at the age of 17, a young Andrew Bolton was already thinking about the possibility of one day working for the Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute. But, before that, he crossed paths with the University of East Anglia, in Norwich, where he was on track to pursue something quite different. “I was actually on track to become an academic”, says Bolton when I ask him about how he became a curator. “I was on my PhD at the University of East Anglia when a job opportunity arose at the Victoria and Albert Museum. I applied for it and was lucky enough to get it. The intention was to work for a year and then go back to my academic studies. But I feel in love with curating, I feel in love with the idea of objects and stories, I feel in love with the idea that every object has a story, and it's up to the curator to reveal that to the public. I sort of feel in love with material culture, and the stories that it could tell.”

“I feel in love with the idea of objects and stories, I feel in love with the idea that every object has a story, and it's up to the curator to reveal that to the public.”

That same passion is one that you can feel in Andrew Bolton’s voice. After nine years at V&A, where he was Curatorial Assistant in the Far Eastern Department before taking on the task of Senior Research Fellow in Contemporary Fashion, 2002 was the year of embracing a new challenge. “It was quite a transition, in a way”, he says about transitioning from the London museum to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “The V&A is a decorative arts museum. The emphasis for fashion and material cultural in general is really focused on cultural studies, to interpret material culture through social studies. So, it was a little bit of a shift.” Since then, Andrew Bolton’s 18 years at the Met went by like this: he joined the museum’s Costume Institute as Associate Curator and was named Curator in 2006; ten years later, and upon the retirement of Harold Koda, he is named Curator in Charge; and, in March 2018, when the position was endowed, Wendy Wu Curator in Charge of The Costume Institute.

Fast forward to the present day and Andrew Bolton has some of the most visited exhibitions of the New Work museum hidden in the sleeves of the exquisite suits that we all associate to his discrete image – including, of course, “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination”, the 2018 record setting exhibition visited by 1.65 million people. It’s not hard to recognize the appeal of the exhibitions that have Andrew Bolton’s magic touch. After all, and in the few minutes that we have been talking over the phone, there is no doubt whatsoever that Bolton is a true storyteller. With so many blockbusters, I ask him what has been his favorite so far. “I have enjoyed all of them in different ways”, he says. “I think that the show that probably was sort of a paradigm shifting show for the Met was the Alexander McQueen exhibition. I think that it was the first time that even the more traditional art historians began to see fashion as an art form. I think McQueen did sort of alter people’s perception about fashion and alter people’s ideas about designers. For me, that was a paradigm shifting exhibition. And I also loved the Prada/Schiaparelli exhibition, which was a sort of fictional conversation between a living and a dead designer. And I think it was very interesting. Even though Schiaparelli and Prada had very different inspirations, and very different approaches, they arrived at very similar aesthetic conclusions. For me that was a revelatory exhibition. And then AngloMania, that was one of the exhibitions where we very much gave a point of view about clothing, historical costume and contemporary fashion side by side. I think that what differentiates our exhibitions from many others is that sort of pairing between the old and the new. I think there is a sort of chronic affect between showing contemporary fashion with historic fashion. I think that AngloMania was a show where we very much articulated that methodology.”

“I think that the show that probably was sort of a paradigm shifting show for the Met was the Alexander McQueen exhibition. I think that it was the first time that even the more traditional art historians began to see fashion as an art form.”

What about the most challenging? “I think they all present different challenges”, says Bolton. “Just when you think you've come up with a blueprint for a fashion exhibition, the subject matter takes a life of its own. I think what I try to do is sort of listen to the subject and let the subject sort of have a life of its own. What I always try to do with all our shows is to be quite light-handed and keep the show open-ended. For me it's important not to be too heavy-handed with their arguments and present it in a way that is open-ended and that people can make up their own minds of it in a way. I suppose the challenge is always to find that balance between a curatorial interpretation and a sort of subjective interpretation.”

Speaking about challenges, we are a few months away from the inauguration of “About Time: Fashion and Duration”, that will be open to the public from May 7th to September 7th. What can we expect? “This one was actually quite challenging, you know”, says Bolton. “It started off with the 150th anniversary of the Met, and all sorts of various initiatives across the museum that are spotlighting the works of art from the Met collection. For me it was important to really look at our collection, to reappraise our collection, and to present an exhibition that was almost exclusively based on our collection. We wanted to share the scope of the collection, but also to create a topic that is timely. I think with all our exhibitions we try to come up with a subject that is timely, that has relevance to the contemporary zeitgeist.” Is there anything more fitting than time? “Fashion is basically the culture of time, it's dictated by time, it reflects the spirits of time and it's actually dictated by the spirits of time. And I think we are all struggling with the ephemerality of fashion, and the defining characteristics of fashion.” How does this translate in “About Time: Fashion and Duration”? “I wanted to focus on an exhibition that was looking at the idea of time and its impacts on fashion, something that is quite timely and quite topical. What we've done is a sort of twin timeline, two timelines. One timeline is a traditional, linear regime of fashion history from 1870 to 2020. And 1870 was when the Met was founded. We are also showing an alternative timeline, which we are calling a sort of interruption. So, the alternative timeline sort of interrupts the linearity of the main timeline, and allows us to rethink the idea of time in fashion, and the notion of duration. What we wanted to do was to create these pairings in a way that show the sort of enduring relevance of the silhouette and technique across Fashion. In a way it's a highly conceptual exhibition, with a number of timelines that allow us to look at fashion differently.”

“Fashion is basically the culture of time, it's dictated by time, it reflects the spirits of time and it's actually dictated by the spirits of time.”

And since we are talking about time, I pick on something that Andrew Bolton told Vogue in 2016: “This idea of fashion 24/7 – it’s not a good thing, I think. It doesn’t encourage designers to step back and have original thoughts”. In a time when it’s almost impossible to talk about fashion without stumbling on the word sustainability, what does the curator hope to see in the industry’s future? “That is something that has been very much on my mind, and I think very much in the mind of fashion designers, which is the speed of fashion. I think that part of the idea behind the exhibition is to promote the idea of slowing down fashion, and to be more thoughtful about fashion, to be more thoughtful about the production and consumption of fashion, and to allow designers the time to reflect on their creativity, and to develop ideas that are long-lasting and have endurance, and are not sort of thrown away.” In a sort of inner thought that the world is lucky to witness, Bolton continues. “Ephemerality in fashion is powerful, but you can embrace the idea of fashions ephemerality in a way that is more thoughtful and more sustainable. I think that new designers are very much heading towards the idea of sustainability, not just sustainability in terms of material, but sustainability in terms of ideas and concepts. I think that what the exhibition is trying to do is to give value to the creativity, and give value to the ideas that designers are coming up with. I think it's really important that we embrace the notion of ephemerality in a way that is thoughtful and sustainable. For me the idea of slowing down the pace of fashion allows to think about and to reflect on the value of creativity in Fashion, which is very important.”

Creativity is a perfect word to define both Andrew Bolton and the long list of exhibitions he has imagined for the Met – but where exactly does the curator find inspiration? “It really comes from all over the place”, he says. “I think that what I try to do more than anything is listen to the zeitgeist and come up with an idea or a subject that I think is relevant to a contemporary audience and to contemporary museum visitors. In that way that is my goal. Foremost in my mind is to come up with an idea that I think will make people think differently about fashion, that will engage visitors and will inspire them. It does come with engaging with the topic that I think is relevant to visitors, that they will find interesting. It's important to have this balance between creating an exhibition that is educational, enlightening and illuminating, but also entertaining. I think that education and entertaining are not contradictory, but more complementary. Every exhibition should have both of them. I think it's important to come up with an idea, but also to present it in a way that is engaging and challenges people to think about that topic in new ways.”

“I think that education and entertaining are not contradictory, but more complementary. Every exhibition should have both of them.”

As I confess to him that this is a puzzling idea, the curator goes further. “I think that a lot of very conservative curators think that entertainment is not worthy of a museum, but it really is. An exhibition should entertain. Exhibitions should inspire visitors visually as much as they do intellectually, and I think it's important to have that balance between the two.” Could this explain why he have seen so many exhibitions dedicated to fashion open all over the world in recent years? “I think people are realizing the centrality of fashion to contemporary culture”, says Bolton about this growing interest. “Fashion is such a complex subject, and I think the power of fashion is that it can reflect the zeitgeist, which is something very appealing to audiences. But also, with the Internet, it has very much allowed fashion to be more accessible, and in a way more democratic, to a wider audience, to a global audience. It has such a positive impact on our field. It presents curators with new challenges because visitors are not much more knowledgeable about fashion. We have to think harder about coming up with subjects that challenge our visitors. But I think it's the fact that fashion is so central to our lives and that fashion can also be complex about identity, and gender, and sexuality, race and ethnicity – it has always been a vehicle to explain very deep meanings about those subjects. I think people are realizing the power of fashion within culture and its central importance to our lives.”

Talking to Andrew Bolton about this industry is like having a free pass, even if temporary, to a world where fashion doesn’t seem to lose its enthusiasm. To a world where we can learn as much from the past as from the present. To a world where each coat, each pocket and each button has a story to tell. With such a long and rich career, it’s hard to resist asking him about the most breathtaking garment he has ever laid eyes – and hand – on. “Again, I go back to the Alexander McQueen exhibition. The opportunity to visit the archives and to select the pieces was really moving. What was extraordinary about McQueen, and I think there is no other designer like him, was that he was able to evoke these visceral emotions in you. He always said that he didn't care if people liked or disliked fashion, as long as they had a reaction. And I think that that was his power, and there has been no other designer like him. It was amazing to honor his legacy in that way.”

Very much like creativity, the six lettered amazing seems to be another word that very much fits Andrew Bolton’s work and the curators eighteen years with the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, and an adjective that has been widely used when talking about both him and his exhibitions. In that same feauture from Vogue, Nathan Heller defines Bolton as “a once-in-a-generation talent who can run his eye over 200 years’ worth of clothing, pick out 100 pieces, and arrange them in a show that families from Duluth fly in to see and that jaded experts find entirely fresh.” This seems to be further proof that education and entertainment can not only coexist, but also be an absolutely undefeatable duo – and that Andrew Bolton really is, as The New York Times wrote in 2015, the Met’s “storyteller in chief”. The curator laughs lightly as I refer this title by the Times and ask him about the stories that he holds most dear from what has been almost two decades with the museum. “I think it really is the objects. I have been so lucky to have access not only to designers’ archives, but also the Met archive. I think that the objects have been the most humbling for me. I feel that fashion is so rich with stories, every item of clothing is so rich with stories, and it's our responsibility to reveal those stories and make them sort of explicit to an audience. For me the joy has always been to look at objects and find their history.”

This article was originally published in Vogue Portugal's Art issue, from March 2020. Para ler este artigo em português, veja a edição de Arte da Vogue Portugal.

Most popular

.png)

.png)

Relacionados

.jpg)