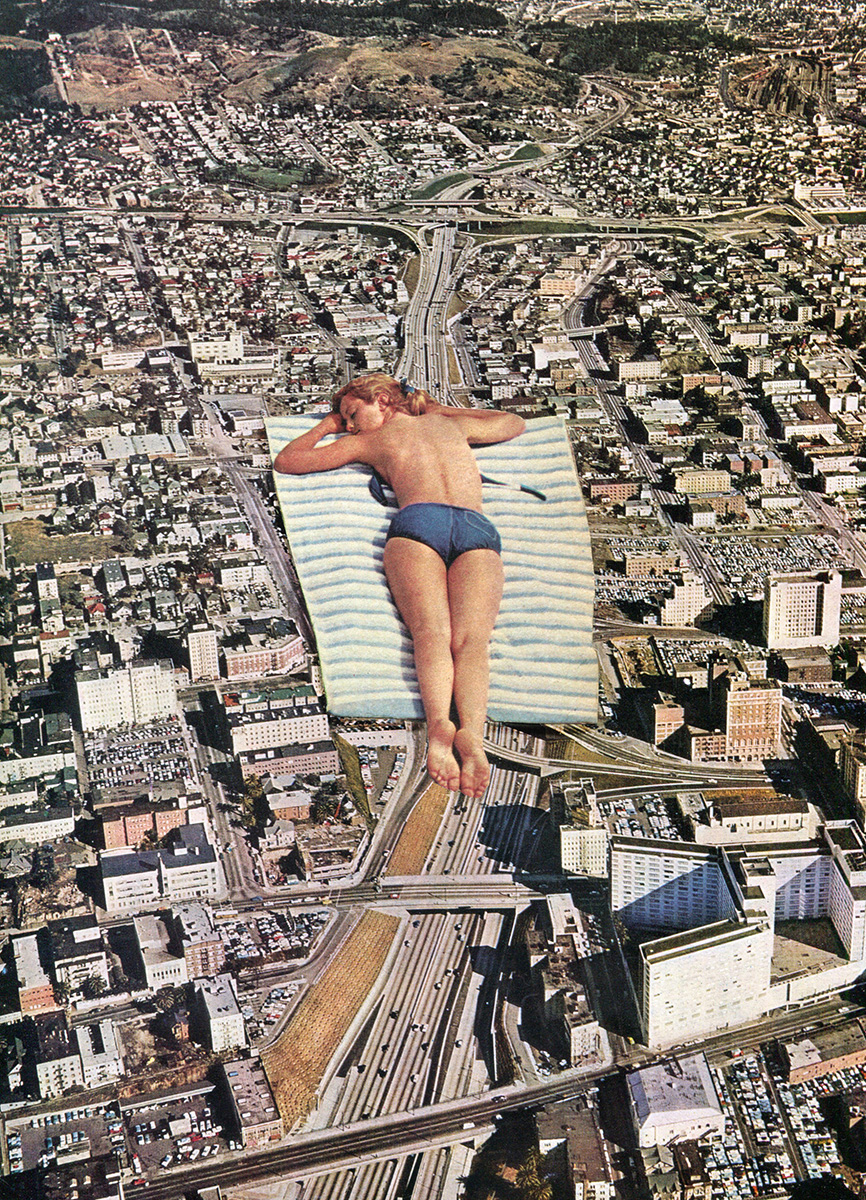

This is a free translation because freedom is what this is all about. To get to the honey that besets the Italian language, at least when they don't look like they're going to clash, with matching gesticulations, one would have to work hard at copywriting. And Dolce far niente is so much more than just that.

This is a free translation because freedom is what this is all about. To get to the honey that besets the Italian language, at least when they don't look like they're going to clash, with matching gesticulations, one would have to work hard at copywriting. And Dolce far niente is so much more than just that.

We are a nation of absent men. Now, because we haveNow because we have always been fighting wars to get the Moors out of here (which I think is bad, because they have given us more than all the dynasties put together, from the irrigation systems to the baths we didn't take until they arrived, whether to enter the mosque or for any other reason than just cleanliness), or to expel the Castilians, or the French, and in the middle of it all things went wrong because a 14-year-old brat had one of those adolescent chitchats and we had to put up with the Felipes. Now because we had ventured to seas never sailed before, in ships that had little to eat and a lot of scurvy, ravenous for spices and gold, changing slaves from continent to continent. It was because Angola was ours just a short while ago and the boys who were the sons of shepherds from the transhumance or fishermen from the xávega art, who didn't want to know anything about Angola, had to "defend" it. The reasons for our absence were countless. The end, was the same: it was the women who carried this country on their backs. Mainly, the mothers. Dressed in black, shawls on their backs or their heads, rosaries in their hands, standing on the top of a dune or a cliff, eyes fixed on the sea waiting for a return that, most of the time, did not happen. It's Saudade, they say. A feeling that is so ours that it cannot be translated into any other language. We are proud of it, it seems to me. We export it as exclusive, produced by the hand of time, we sing it accompanied by the Portuguese guitar that has a wave where the strings are tuned, it says that it is fado, destiny, and here we go, with our heads between our ears, with the future pledged by something that goes on inside but that even we don't know how to explain, always poor, always honorable, as if honor were the only thing left after a piece of bread and a rarefied soup, bedwetting, that tomorrow is another day. This is the image that Portugal seems to want, too often, to convey. But the truth is different. Not least because times have changed. Perhaps it was with the 25th of April that the black cloak that covered us was removed, that Sword of Damocles that hung over us, repression lurking on every corner, a snitch in every building, all it took was not liking us and turning the dial on the telephone to tell the PIDE that "these are people who have subversive meetings at the weekend" and there we were slapped in Caxias, maybe Peniche, maybe Tarrafal. Today, all we need is a glimmer of sun, the sun that shines in the South two-thirds of the year. Today, all we need is a spot of sun, the sun that lights up the south two thirds of the year. What we want is the beach, a terrace with snails, drinks with friends, well-watered dinners, music festivals, vacations in the country, vacations on the coast, seafood, vinho verde, in short, regabofe. While there are no vacations, we have to pray for the weekend, and when it comes, nobody prays, Sunday is not for receiving communion, it is for "laureating the seed" with the same love for life that the emigrants return with to grab, during the month of August, the life that seems to escape them when they are on foreign soil. Give us a trellis and a table underneath it where there are demijohns, bag in box, cold beer, grilled entrees, sardines, and plastic bags full of water hanging on the rope of the clothes to scare away flies. The children run free behind the dogs and cats, the parents forget about them because they have had enough of all the other days, there is shouting and vernacular, it is a scene worthy of a film by Emir Kusturica but with less gold teeth, that is for filigree and what you take from this life is this, that sunny morning that went on late into the night until someone remembered that there could, by some misfortune, be stop operations. How sweet life is, as sweet as the Tentúgal pastries, Jorge Sousa Braga would say.

Dulcissimo do niente gets, in Italian, much better. Dolce far niente no longer sounds like the Nissan Vanette that, on the way back from that religious act that is "going to the land" (and that is probably why it happens more at Christmas, Easter, and in August), comes full of potatoes and onions and jugs of strawberry wine. But it's all the same. Latinos like us, Italians don't make "none" because the mamma and nonna wake up at 7 in the morning to start kneading the pasta that will be gnocchi con patate by 1 pm. Why do they wear a well cut suit on Sunday instead of getting into a slick tracksuit, bought at the Feira do Relógio, to go "with the kids" to eat a McChicken at Colombo. Why do they go in a Ferrari or Lamborghini where they have to go? Of course not! They also go by Fiat and Lancia. They also drink beer, not everything is Negronis and Aperol Spritz. They also sit, like us, on a park bench, reading a book. Or the sports newspaper, to know the opinion of experts about the game they watched the day before, just like us, biting our nails. They also gather with their families at the weekend, under the shade of a vine, for a meal that starts at lunchtime and doesn't end until late at night, between games of Swedish or dominoes. They also take long walks to "un-moderate" the meal, as long as there is a forest or field. In fact, what happens to us, in this Mediterranean strip that still grabs us by the feet in the Algarve, and that can be called cultural, or at least guttural, is the propensity for contemplation.

It is not a question of whether some contemplate the sea (in that wait for something that will never come, with or without the shawl), and others the snow-capped mountains that baptized them as transalpines or the everlasting Vesuvius that has even given them some trouble. We have in common the origin of our civilization, due to the Greeks who strolled, with all the calmness in the world, through the Agora, sometimes deep in thought, sometimes in pairs or in groups, discussing the issues of the day. In a first, more simplistic analysis, being a philosopher was a profession. Ultimately, this is how democracy was born. And, after all, all we needed to create a political system so genius that it is still sacred today (so much so that some people want to do away with it), was to relax, hang out, and exchange some ideas on certain subjects. Yes, if we sit down, relax, look at the horizon and dwell on this subject long enough, it is easy to come to the obvious conclusion: work is what screws us. Hence this Latin desperation for the work day to be over so that we can give ourselves to the reason why, after all, we are here: the sweetness of doing nothing! It is unfair that the dolce far niente is the exclusive property or trademark of/for Italians. As if the Alentejans weren't famous for their naps in the shade of the chaparro (try it, it's delicious, just ignore the lupine spiders, jumpers that they are). As if the Spaniards didn't need a siesta, with their Andalusian blinds up, to replenish that energy. As if the French from the south didn't suffer from the languor that a glass of wine from the Provence region lends to a stroll through the lavender fields or a liqueur from Cassis (just outside Marseille) in the late afternoon, on a terrace by the Mediterranean. This is precisely what Paolo Sorrentino, a film director (who as far as creativity is concerned is only just beginning), tried to demonstrate, in my opinion (but isn't that the wonder of cinema - or of any art other than the seventh, to interpret it our way?), when he directed La Grande Bellezza (2013), winner of the Oscar for Best Foreign Film and the Official Competition at Cannes. Jep Gambardella (Toni Servillo) decides at his epic 65th birthday party that from then on he will only do what he wants to do. In other words, he will not do one more freight. This epic bender, held on the terrace of his house overlooking the Colosseum, where the cream of Roman social and political life is, which is the milieu where he moves and dominates since glory has befallen him with the publication, decades ago, of his only novel, ends with his best (or only?) friend and publisher, who suffers from dwarfism, calling unsuccessfully for Jep. But this one is already engaged in his favorite activity: walking through the streets of Rome, driven by melancholy and dressed in his clear suit of impeccable cut, haughty pose and sophisticated manners, to watch her rise with the sun, the one that lends her that oblique light that so inspires his wit, a pointed weapon he uses to criticize all the vanity, decadence, loneliness and hypocrisy that rages in the modern Rome he knows like the palm of his ever-hydrated hand: "What ulterior nonsense Stefania! Did you know that Flaubert wanted to write a book about nothing? If he had met you, we would have had a great work, what a pity." Only after this does he return to his sumptuous apartment, to rest precisely at the hour when the Italian capital belongs to a bustle he is unaware of. It is from this pedestal that he encounters, throughout the film, the most ambitious, deluded, and frustrated characters (worthy of the felliniana tradition) to conclude that life, as ephemeral as beauty, is totally devoid of any greater meaning in contemporary society. Which leads him to return to his native Naples, the one that lends him the accent that is noticeable in each tirade, always loaded with a poeticism that once characterized European cinema, such as "What's wrong with feeling nostalgic? It's the only distraction left to those who don't believe in the future" or the epic beginning of his novel: "This is always how it ends. With death. But first there was life. Hidden under the blah, blah, blah. It's all settled under the chatter and the noise. Silence and feeling. Emotion and fear. The tired fickle glimpses of beauty. And then the blasted squalor and wretched humanity. All buried under the cover of the embarrassment of being in the world, blah, blah, blah.... Beyond that is what's beyond that. I don't deal with what is beyond. So... let this novel begin. After all... it's just a trick. Yes, it's just a trick." Il dolce far niente, as an ulterior way of life, has to have a meaning. If only to seek the meaning of dolce far niente. So that it continues, nowadays, to make sense.

For this we had (and we have, because lucky for us, the man wrote), Agostinho da Silva. For him, human work should be linked to creativity and should be a fulfilling activity, which allows the individual to express his or her talent, with the aim of contributing to the well-being of the worker but also of society as a whole, not an obligation aimed at making money, which serves only to allow us to live the little we have left. Routine alienates. It kills creativity. And, according to his analysis, it all starts at school. Where memorization and reproduction of preconceived concepts (that someone has already "thought for us") are valued, to the detriment of creativity, critical thinking and, therefore, a deeper understanding of the world we live in. Nobody explores, from school to work, the creativity that would allow, according to our (perhaps only) philosopher, that one day we would be that poet on the loose that he wrote so much about. The man, free of any ties, who thus becomes what he was created to be: a highly sensitive being, with an unbelievable potential, able to be in full communion with nature and other human beings to the point of making this world a full place. In other words, it is the defense of the sweetness of doing none as a means to reach fullness. The one that has to be born in the complete lack of need to be busy with activities and tasks, let alone the sense of duty instilled by a job. The small pleasures in life, like enjoying a good meal with all the time in the world, a contemplative walk in nature without haste, a nap in the afternoon breeze with no time to wake up, a drink at the end of the day that may or may not turn into a leisurely evening are still possible things. That is why the law that forbids bosses to contact their employees outside office hours was passed. Do they comply with it? So why should we keep to schedules? It's not a matter of civil disobedience. It's a matter of survival. Otherwise we will reach the end of our lives without having lived them. Jep Gambardella has decided not to charter any more freight after the age of 65. Only before that, he was Jep Gambardella all the time.

Originally translated from The Pleasure Issue, published May 2023.Full stories and credits on the print issue.

Most popular

.png)

.png)

Relacionados

.jpg)